My House Is Your House

WHO ARE THE PEOPLE FILLING NEW YORK’S HOUSING COURTS?

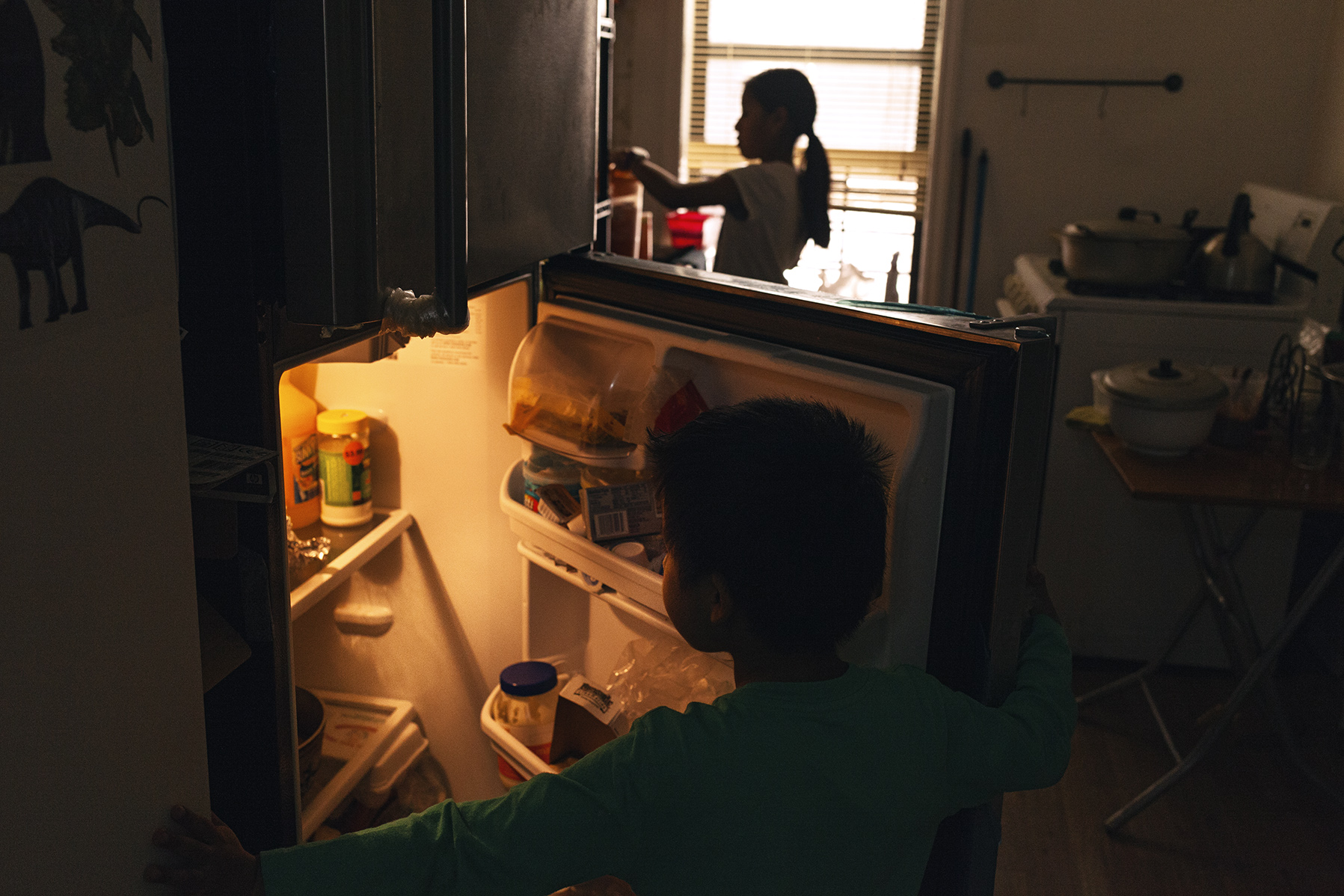

Samantha Bravo was eating lunch with her younger brother, Nathan, when she heard someone slamming at her door. She knew who it was. It was someone who frightened her.

The woman stormed into their Sunset Park apartment, screaming at their father, “You are so stupid! You only complain! Fuck you!”

She cursed him, over and over again. The kids watched, without understanding why this was happening. Nathan ran to his room and hid, crying in panic.

That was three years ago. Nathan was 2 years-old at the time, Samantha was 9. She is able to walk through every detail from that event. That day was marked in their memories as the beginning of a battle against their landlord that continues to the present and denotes the excesses that are so common in eviction practices and methods.

Nora Huertero, their mom, wasn’t there that day. She was working on one of her shifts as a house cleaner. She works double-shifts to support her family of five but that is barely enough to keep her in the apartment: over 70% of her income is devoted to paying rent. They are part of the “severely rent-burdened” families. Nora came from Puebla, Mexico, 23 years ago and settled in that very apartment. That was her home when she got married; it housed her three kids since birth.

New York currently has its largest housing stock since the 60’s, yet more people are left on the streets. “Within DeBlasio’s administration, the median gross rent rose 4% while it had historically changed by 1% from 2006-2013. Maybe this explains why this administration has had the unprecedented homeless crisis. Not because evictions rose, but because rents rose much faster than income, making housing unaffordable and unavailable”, read a Furman Center study. Brooklyn, for example, became the least affordable borough in all of the U.S., surpassing even Santa Cruz County, CA.

Housing affordability is essentially an income problem that relates to the creation and maintenance of poverty: affordability for the working poor has fallen in a straight line for the last 10 years. Nearly half a million New Yorkers spend more than 50 percent of their salary on rent, and an overwhelming majority are low income families.

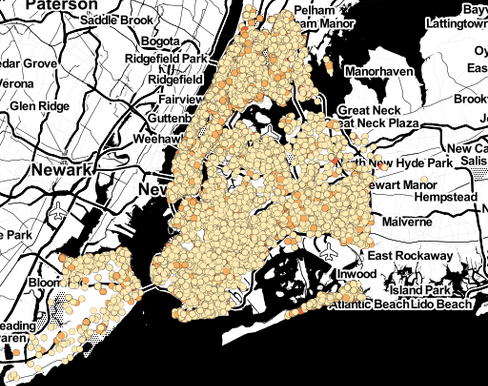

Displacement has become an inherent characteristic of big cities, or a product of economy that cannot be contained. The numbers are there: around 300,000 people face risk of eviction every year. But the effects of living without a house cannot be put into numbers, it is a condition that often defines the type of life a whole family will have. It is important and a lot less documented who exactly are those people squeezed between the growing wealth of the city and the housing crisis. Over 60,000 people will be sleeping in a shelter tonight, almost half are underaged. It is possibly the highest number since the Great Depression.

This is not surprising anymore.

Evictions, the number one path to homelessness, are so common these days that they are seen as an unstoppable consequence of the housing market while the poorest take the hit.

Chloe barked without rest when Nora Huertero opened the door of her Sunset Park apartment. “That’s my baby”, Nora said, while the puppy jumped and wiggled the tail. “We adopted her so that the kids would feel safe, because they’re so scared of that woman and Chloe doesn’t let her near this place.”

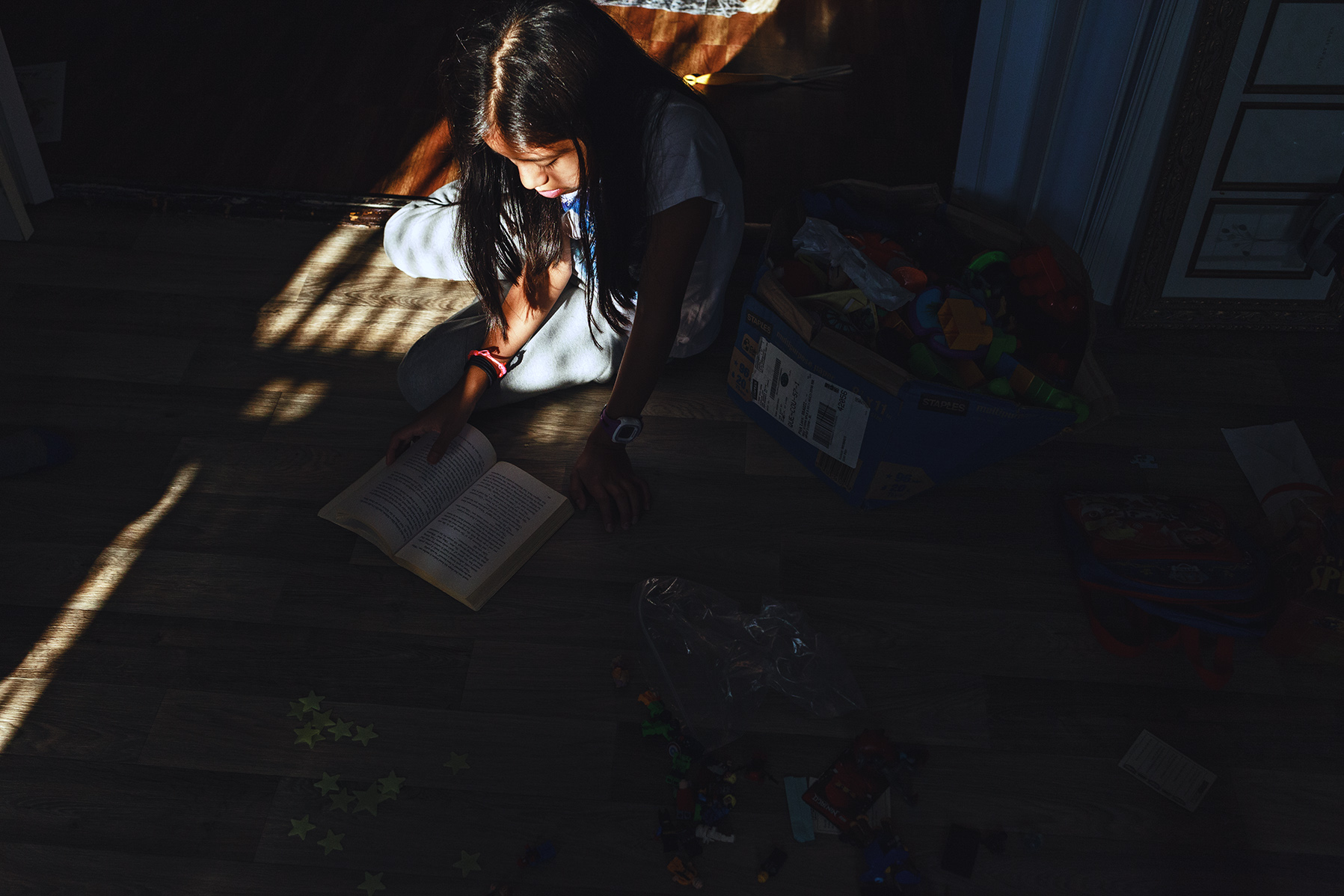

“Oh! And my other baby is right here!” she squatted under the living room’s sofa and a small head popped up, eyes wide-open, staring with distrust. It was Nathan, her youngest son. He was hiding because any talk related to their landlord frightens him. Samantha, her middle daughter was reading a book while resting on her father’s shoulder and Donato, the eldest, was reading on the computer. They all sat together in the living room and shared the day.

Nora had never complained about the conditions she lived in before even though her landlord and the appointed superintendent called them “pigs” and threatened them to kick them out every now and again. She didn’t want any repairs to her apartment because the landlord would raise their rent to an unaffordable price, so they had to fix the broken floor of the living room and invest their own money on the sorts of things that would commonly be handled by the building owner. In a way, she thought that aspiring for a better life could only get her in trouble, that there was no way to win against someone who had so much more money than they did. Nora didn’t know that what was happening to them was illegal.

One time, the landlord told the family that they shouldn’t call 311 to make complaints because they didn’t have such rights: Nora and her husband are undocumented immigrants and were scared to speak up at the beginning, fearing any government intervention might put them and their kids at risk. Legally though, Housing Courts cannot contact Migration Services to ensure people living in New York can still have basic civil rights, regardless of their migration status.

Families that don’t speak English or don’t have U.S. citizenship are the most vulnerable and targeted communities. Landlords use everything in the toolbox to get them out: they try buyouts, they make it so that apartments are unhabitable, they take people to court until they dry out.

Meanwhile, companies such as quickevic.com and kickemoutquick.com are on the rise. They define themselves as a “One-Stop-Shop for landlords” under the promise that “After your eviction is complete our collection partner, Express Recovery Services, Inc. will aggressively pursue your ex-tenant for the money that they now owe you.” Both companies refused to comment upon contact but have been accused of engaging in extreme forms of harassment to get tenants out and collect money.

It was a Saturday afternoon, the only day Nora has to spend with her three children and her husband. She went back and forth from the kitchen to the living room, making tacos al pastor, and the kids were happy. Her mom and grandmother had worked most of their lives selling food on the streets of Puebla. “The kids love Saturdays because I cook for them.”

She recalled the one time she found a poster of Neighbors Helping Neighbors, a counseling agency devoted to empowering people facing harassment and eviction, and contacted them. “They taught me and my family to stand up for ourselves and demand that we be treated with respect”. Nonprofit and civil organizations tend to be the last resort for families on the brink of despair and, for most part, they help families stay in their houses.

“The floor and walls had holes, the windows didn’t close, water leaked from the ceiling… we could go weeks without heat or hot water. To her we are like dogs...” -- her stare was fixated on the wall as she recalled what her house used to look like a few weeks back. The building gathered over 600 complaints before eight families took the landlord, Soo Fung Dong, to court with assistance from the Urban Justice Center. That was the first time Nora faced her landlord in Court.

“What you’re doing is criminal! If you don’t like it here, move to Manhattan!” said the landlord in a voicemail.

The voicemails played and became increasingly aggressive. Her landlord was not happy about losing that lawsuit. Meanwhile, Nora sat on her newly renovated floor and hugged Nathan. That floor was not any floor: what is a given to some, is a privilege to others. She had waited over a year to have it fixed, had to take her landlord to court and protest outside of her building after the court ruled in her favor because the landlord refused to make any changes. Nora was proud of her floor: it was her own accomplished battle for a better life and the dignity of her family.

“We wanted to live better and it almost got us out of our house,” She said

The sterile walls added up to the anxiety of the line, which extended for blocks and blocks and was filled by women of color for the most part and Orthodox Jews for the other. The stairs and halls were packed with people breaking into tears.

“If we don’t unite, they will keep doing this to us! We will fill these rooms forever! We need to come together!” a woman screamed, despaired, in one of the waiting rooms of Brooklyn’s Housing Court. People stared at her, confused, because the vast majority don’t really understand English and are utterly confused by the procedures or the reasons they’re there for. Most of them just lined up behind each other, not really knowing what the lines were for. This place, this state of mind, is an everyday reality for thousands of people in this city. Housing Court could only be compared to hospitals: sterile hallways, poor-lit stairways, filled with worried people that cannot think of anything except running away but cannot, they have to be there, expecting the worst. This becomes a condition that lasts years, to oftenly end up in the place they feared most: outside of their home.

The Huertero family looked for help at an early stage of the case, which is defining. Most tenants arrive to organizations when their cases are way too advanced to make any difference and, since people don’t live their lives in constant fear of being evicted, they rarely keep substantial documents to make a case for themselves. Housing Court battles take place on uneven grounds: poor people tend to get the shorter side of the stick, with no money to pay for an attorney and no clue of how to navigate the legal system.

Eventually the day arrived.

It was around 10 p.m. and Samantha was about to go to sleep when someone knocked at the door. When she opened, she was served with an eviction notice, stating that they had to move in three weeks. It was a Non-Payment procedure, the most common of cases in Housing Court.

“Mom, are we gonna have to move?” Samantha asked her mom.

Baseless eviction proceedings are a common starting point when a landlord wants someone out, and that’s how Nora’s family ended up in Housing Court for the first time in 2015. They proved that the payments were made but the landlord did not cash them out and won the case within a few weeks. “We just wanted to have a good life, to have a nice apartment... instead, I lived in anguish and couldn’t sleep at all. I was miserable just thinking of the idea of not having a home. Where would we go? I don’t even want to think about it.”

This is a reality for over 20.000 families getting evicted every year.

The overwhelming majority is below poverty line and having to wrap their heads around living on the street or in shelters, which have waiting lists that could extend for months. This is how evictions look like in New York:

The map does not include data for illegal evictions. Author: Adriana Loureiro Fernandez with data from https://nycopendata.socrata.com/

Nora’s apartment was supposed to be one of those dots. “Court is an emotional distress, it takes such a high toll on you and your family”, Nora recalled those days vividly while her voice stumbled, “I could only think… Is my life worthless, is my children’s life worthless?”

Fabian Bravo, Nora’s husband, played with the kids surrounded by piles of documents that were neatly arranged by date. He took care of documenting everything, from calls to gas receipts, to make a case for them in Court. He had become extremely familiar with the legal jargon, being able to walk anyone through every step of the way: “It isn’t over yet. Most of our cases are still open and I think it will take some time, but we have come a long way”.

Fabian used to work near Columbia University and, even though he didn’t understand much English, he always picked up some lines: people talking about how one name was different than the other, how that affected the eligibility for students and workers. “I’m not ashamed of being Mexican at all, I just didn’t want my kids to be left out of anything because of their names on a list, that’s why we named them like that: Samantha and Nathan”. He picked names that weren’t explicitly Hispanic because he wanted to protect them from racial discrimination. Yet still, discrimination did not affect them at school, it affected them right there, in their home.

Nora’s landlord could not succeed at emptying the apartment because they were represented by Camba, a nonprofit organization that provides legal counsel to low-income tenants in Court. This is a rarity. In Civil Court, the poor have no right to counsel so an overwhelming majority of tenants go through this process on their own. “People end up leaving because they don’t want to fight anymore. They give up. The landlord wanted to scare us too but I don’t care if I have to work double shifts to support my family. I’m just glad we have a home,” Nora said.

“As we face one of the most serious affordable housing crises in our city’s history, we have made an unprecedented commitment to provide legal assistance for low-income New Yorkers, and we are beginning to see the results of these efforts,” said Mayor Bill de Blasio in a press release.

Indeed, the City invested almost $50 million in tenant legal services and plans to invest more the next year. It has proven to be the only successful attempt at tackling homelessness from a preventive approach, instead of a regulatory one. Nora’s family is a living proof of those achievements. “If they (her legal advisors) hadn’t been here, I wouldn’t have a house. I’m sure we wouldn’t be here anymore,” she said.

A recent report concluded that the City could save hundreds of millions for passing a bill that would ensure the right to counsel for low-income tenants in Civil Court and keep over thousands of families outside of the shelter system.

Nora came back from the kitchen. Lunch was almost ready and the kids were setting up the table. “If this has been so traumatic for me, I don’t know what it is like for them. They’re just kids, they shouldn’t be going through all of this”, Nora said as she looked at them.

“I really don’t know if this is good for the them. Samantha has learned so much though…” Samantha became very involved with the process from the beginning. She translated to her parents all the voicemails and letters their landlord sent, which often involved cursing and threats of eviction. Samantha is a strong girl who thinks way ahead of what any other twelve-year-old might think. She spoke with a soft tone but sturdy words, she’s had to speak and defend what she believes are her family’s rights and her own. Her mom is proud of that.

Nora never expected to face the possibility of homelessness when she arrived to New York, specially not after living and working there for 23 years, but her family became the typical representation of those numbers shown on charts and statistics, the ones making the lines in New York’s Housing Courts: a working family that, like thousands, had to fight to keep their apartment and succeeded greatly because they had legal representation. This made the difference between having dinner in their house, or in a shelter. Her battle is not over though, she is certain that this is not the last time they will be summoned to Court.

Dinner was ready and everyone gathered. Nora came out of the kitchen with a big plate overflowed with tacos. The kids were happy. “Pizza-Taco! Pizza-Taco!” Nathan yelled and made everyone laugh. There was a sense of caring contained in that dining table, capable of taking many people back to their youngest years, the ones that define a sense of belonging and safety. This is one family that got the chance to stay together. Most don’t have that privilege.

Nora stood up with a smile, “Feel free to come any Saturday for lunch. Next time I’ll make pozole. You know how we say, ‘Mi casa es tu casa’”.